by Barry Keane

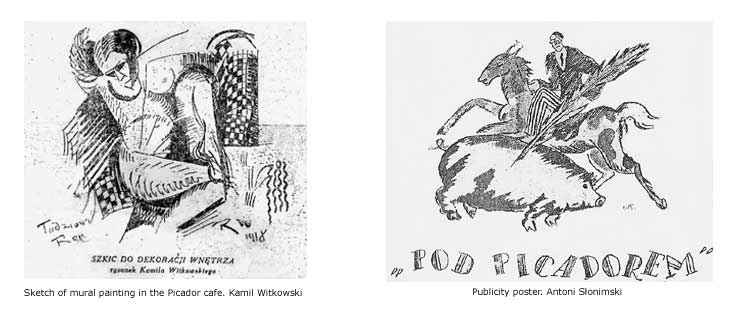

On November 27, 1918, Poland’s independence was

celebrated by the inauguration of a poets’ café in Warsaw.

The poets themselves were five and within a year would

collectively call themselves the Skamanders. What follows is

an imagined account of an evening’s performance based upon

a little knowledge of the poets and their early works.

* * *

Wet upon the ground and damp the evening air —

All inside looked to the corner,

Where they sat and made ready.

Some elder poets sat small and wished the world away,

Some sat smaller, and brooded.

And the world gathered to their call:Artists Unite. Poetry For The Street, and the declaration:

Long live us all. People of Warsaw, the learned, the stupid,

The young and the old, most women and the rest of them,

The rich, the poor, the titled, the homeless, actors — good and bad —

Bad poets, good listeners, wielders of scissors, shovel or sword,

Maidens with money, wealthy wives with death-bed husbands.

All here eating cake…sipping tea.And Antoni Slonimski rose to address those sitting before him:

Ladies and Gentlemen, and the Rest who have come,

You’re here for something different, some call it fun.

But be warned, take care, for it’s bruised you’ll leave,

You’ll be stripped of what you know by our songs,

By this new voice of youth which tramples the street,

Shaking hands with the many or as many we meet.

You are our subject, so the choice is plain,

Raise your head sky-high or hang it in shame.

It’s a damaged lot I see before me tonight,

Whose parent and grandparent and great-grandparent

Spent long years bewailing our country’s long night,

And spoke of the need to fight and draw blood.

‘Death is glory!’ they cried, as they faced what they faced;

Spring was black and summer cold.

Tonight we see the world

Through different eyes.

We breathe different air,

Our first free spring is in the air.

Though perhaps not in here.

Sit closer to the door, you two!

Your pungent smell will certainly upset

My friend, shaking behind me here,

Set to set the record straight.

Jan Lechon, our youngest poet.And he who was youngest took his place on the podium

To the sound of polite applause. And pale was he:Our Polish heroes are dead. What would they say now?

Fight on! Find foe and cannon!

Take them on!

Run them through!

Attack! There is no nation without blood spilt!

There is no art but that which makes you bite your lip

And swear death on the foreigner swaggering in front of you!

The present moment flies in the face of this call,

And our motherland has no foe but her leery brood.

We are the enemy within these walls, slashing

Wrists with heirloom-gilded table knives.

Look at the devils in our midst — our holy rites,

Look at the shackles on our feet — our sacred myths.

Murder is abroad on the night, O Citizens,

And our luckless past and glorious future are locked

Together in a struggle.

Our sacred memory and texts will not build our nation.

They will not inspire a nation of nation-builders.

Look out the window.

What do you see but a lost and leaderless lot.

Yet the great streets are rising,

The scream of the thronging crowd will be whispers,

But the stars will reverberate from their echo.

Mothers will shed soft and silent tears,

And trumpeters will play their part in the day,

Playing notes that choke with affection.

And horses will tramp loud upon the ground,

And the cavalry will laugh gallant,

And we’ll ring the bells with all our strength,

The priest, in red and gold, will raise the host twice,

And the people will bow their heads and be satisfied.

Banners! Banners! And he whom we love, dressed in grey,

will sit silently upon his horse.The poem complete, he who was young turned his back on

the crowd and returned to his chair among his companions.

And a man from the audience stood up and said, ‘I

understood not one word. But what a poet! Who’s next?’ And

Antoni Slonimskiso so spoke, ‘Your taste is a credit to you, Sir.

It is beautiful, is it not, to not understand one word and still know

what a man means? The next is a devilish sort with a twinkle in his eye.

Ladies and Gentleman and the rest of you, I give you that

stirrer of controversy, Julian Tuwim.And Julian Tuwim, the stirrer of controversy, stood up

and launched into the following:I see the world with my million eyes, and

Each absorbs the world. The world is in me and I in it.

It is all I and what I see. And what I see makes me bigger,

And makes what I say more important. So hear what I see

And let’s see what you think, and then we’ll see what next to do.

Listen now to the drunkard’s song out in the street

And he and they, sloshed and buzzed and floating off somewhere,

Banging the bar-table with a strong fist,

Searching for a little brightness from gloomy days —

Smashing everything.

Freedom! they cry. They’re right! I’ve power!

Run spirit till dawn. Today we rule!

We’ll stagger wide down the drunken street, nobody’s fool!

The city’s a symphony-roar inside my head.

I’d catch the moon if I could

And present a petal of it to each of my seven women,

Whose legs fly high seven days of the week,

Looking to populate the place – on the grass if need be.

No rest for this worker. Make way. I’m on the hunt.

With that the café erupted in an outcry and a red-faced man so said:

‘Easy there, young fella, there are ladies present.’ But

Tuwim to this: ‘Truth’s a poke in the eye.’ It was all

Slonimski could do to prevent pistols at dawn. But in the end,

the offended party was mollified by a signed copy of

Tuwim’s first poetry collection, which the stirrer of

controversy had kindly dedicated to the man’s wife. And the

audience applauded the right action of each side.

‘Well done, Gentlemen,’ said Slonimski, ‘you’re better men

for having quarreled and settled the impasse. Now indulge me

for a moment as the power takes its grip and I launch into a

modest piece which has cost me no end of sleep’:I feel a world inside me which spins on its axis,

And my breath is an interplanetary wind,

And my touch regenerates what is lifeless.

I absorb the sun and see that laws are founded

In the movement of those truth-bending stars

And the slow-revealing harmony of silent,

Places, that beg to be silently drowned

With low whispers that none can hear.

My world is a slave to an unearthly power

That strikes it with flame and burns palaces,

And where the stigmata reveals what is his

And robs sweet time from my silken grip.

What may I do but chase it to the darkest places

And call to the Northern Lights in my quest,

ever calling —

I’ll set the time of my life.

I’ll send a fiery arrow through the black.

I’ll set the conditions of my rest.With that the face of Antoni Slonimski went pale, and the poet

leant against the nearest wall. ‘Outdone myself I have. I think

I’ll sit down. Welcome now a Ukrainian blow-in who sings

the wisdom of the aesthete in lines of eight, Jaroslaw

Iwaszkiewicz.’ And the Ukrainian poet so spoke:Take my blue hand and draw your eyes so…

To grassy gardens, a flower-blooming meadow,

Splashing your eyes with the spring’s morning dew,

Warming your cheeks on sunbeams, bursting through

The veiled sky, plunging into the stilly lake waters.

And your ears will hear the rise-rippling callers,

Making their voice ever louder in rumbling humming bass,

Staking a claim on time in impressionist picture-space.And the poet, having sung so little, had little else to say, but

was pleased all the same with the polite applause. It was clear

that his words were not alien to the proceedings, and he was

happy with this. Indeed, the café approved of the mention of

lazy sunny days and trips out of the city on that cold night

And Slonimski stood up and addressed the audience - ‘Sun’s

a marvellous thing. But we’ve had too many cold years to be

waiting on a season’s humours. The floor is best taken now

by a man who possesses a happier disposition than most. For

the ladies and the rest, I present Kazimierz Wierzynski. When

he’s said what he’s going to say, you all must drink up and

get yourselves home.’ And Wierzynski leapt forward:It is clear, is it not? –

That I could leap

From one mountain-top

To the next,

That I’m the spring sun

Drying the pavement

On this dreadful night,

That I’m the baker

Baking trembling doughnuts

In the oven.

The world is so fine

And I so handsome,

Standing here sky-high

In this new suit,

Parading proudly and smoking

The right cigarette.

And I nod to the slender

Ladies with their longing eyes,

Come with me now,

Let us stroll through the city streets

Hunting skies reflected in puddles.

Come with me now, out of this place,

And let us find a meadow

Where the ground is warm under blanket

And the wind whispers, and

The cows low, and the sun pours

Gold into our eyes,

As our heartbeats quieten

And our features soften,

Surely something

In these Arcadian days.With that the night ended, but not without shouts

from a dissatisfied sort, who wanted the final say. And have it he

did: ‘You sun-obsessed lot! It’s too many months to go to

spring. Tomorrow it’s bad weather and grinding work for the

lucky ones.’And with that history fell away…

Barry Keane was born in Dublin in 1972. He is a Doctor of Polish literature and teaches literary translation in the Department of English at Warsaw University. He is the author of acclaimed works on the Polish Renaissance poet, Jan Kochanowski, and the Polish modernist Skamander poets. In 1997 his translation of Piotr Tomaszuk’s 'Doctor Felix,' performed by the Wierszalin Theatre, won first prize at the Edinburgh Fringe Festival. He has written one previous book of poetry entitled The Crystal Side (1998). This poem is from his forthcoming collection called Inshore, published by Shoregate Press.